Leaseholds should be Regulated like Financial Products

Recently I’ve been passively looking at property for sale. Once a day Rightmove sends me a list of properties in London that have been put on the market in the last 24 hours. An infuriating part of this daily ritual is checking each property to see if is a leasehold — but sometimes that information is hard to find.

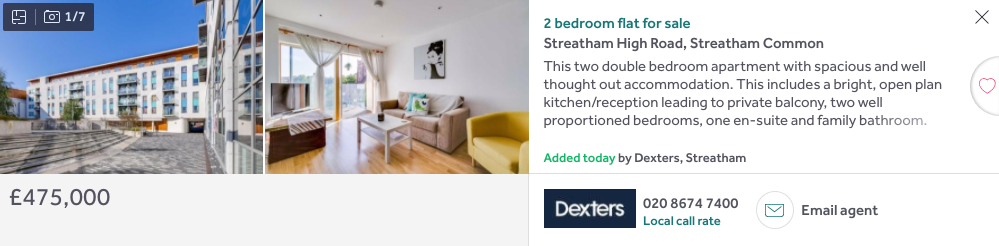

Two bedroom flat for sale in Streatham. Is it a freehold or leasehold? The only way to find out is to call the agent.

Leaseholds in the United Kingdom

In most of the world when you own a property you own the land, the building, and the rights to that property indefinitely. In the UK we call this freehold. The reason we have a special name for “normal” property ownership is because we also have an alternative, feudal form of ownership called “leasehold”. With leaseholds you don’t actually own the land or the building (the “freeholder” does), you only own the right to it for a set amount of time — typically 100-1000 years. Usually you also pay a yearly rent called ground rent (typically £1-£1000) as well as maintenance charges for the upkeep of the building. Since you don’t actually own the building, there can be restrictions on what you are allowed do with the property — for example you might need permission from the freeholder (landlord) to keep pets or make renovations. Although leaseholds continue to be sold in England and Wales, they were banned in Scotland in 2004 and “defanged” in Northern Ireland in 2001 where leaseholders have the right to buy the freehold for 9 times their annual ground rent.

The Leasehold Scandal in England and Wales

In 2017 58.5% of all new houses were sold as leasehold despite 17.9% of housing UK being leasehold at the time. The reason for the popularity of leaseholds was that housing developers had seen them as an important additional revenue. The freehold rights to leasehold properties are big business. Leases with onerous clauses for ground rent increases (often doubling every ten years) are highly attractive to investors looking to beat inflation in a world of low interest rates. Buyers are typically institutional investors such as pension funds. Great for investors, but terrible for homeowners — ground rents can sometimes increase to such an extent that the property becomes worthless. Known as the “leasehold scandal” this practice was widely reported in the media in 2017. In response to the scandal, the percentage of new homes sold as leasehold has dropped significantly (4.2% in England and Wales in 2018) and the government commissioned an investigation into reforming the law which is currently ongoing.

Freehold Rights as a Financial Product

For investors, freehold rights are a sophisticated financial product: Leases have a wide variety of clauses around how rent is paid, how and when it can be increased (for example doubling every X years, or in line with RPI), how long the lease lasts, what happens in the case the leaseholder doesn’t pay etc. In short: they are complicated, diverse contracts and valuing them is a complicated process with no “one-size-fits-all” formula. They are generally sold to institutional investors and not the general public (unlike say, stocks & shares). In fact if you did try and sell freehold rights to the general public you would be met with a litany of restrictions from the Financial Conduct Authority on how you could do it. For example, peer-to-peer lending platforms such as Funding Circle can only do business with individuals who are classified as:

- High-net worth investors

- Certified “sophisticated” investors

- “Restricted” investors who will invest no more than 10% of their assets

ie, people who either understand the risks (sophisticated investors), can afford to lose the money (high-net worth) or aren’t investing enough to take on much risk (restricted investors). These restrictions are for marketplaces where personal and business loans are bought and sold — arguably a simpler product to value and understand the risks of than freehold rights.

So freehold rights are a complicated financial product that, if chopped up and sold to the general public like a peer-to-peer loan, would certainly attract scrutiny from the FCA (if they were even allowed to be sold at all). However the other side of these contracts, the leasehold is sold to the general public tens of thousands of times a year with almost no restrictions on how they are marketed. There is ample evidence that people are buying leaseholds without understanding how ground rents might increase, the burden of administrative fees, or how the terms in these contracts can affect the resale value of their homes.

A leasehold is a contract that:

- Requires you to pay an regular fee (ground rent) for the rights to a property

- Restricts your use of the property

- Can lead to losing the rights to the property if you don’t comply with points 1) or 2) (for example this man who redecorated his bathroom).

If you squint hard enough this kind of looks like a mortgage! As you might expect, the sale of mortgages is regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. In fact they have a handy 582-page document called Mortgages and Home Finance: Conduct of Business Sourcebook to help lenders sell mortgages responsibly. More generally, the FCA is guided by the following six “outcomes” in its regulation of financial products:

- Consumers can be confident they are dealing with firms where the fair treatment of customers is central to the corporate culture.

- Products and services marketed and sold in the retail market are designed to meet the needs of identified consumer groups and are targeted accordingly.

- Consumers are provided with clear information and are kept appropriately informed before, during and after the point of sale.

- Where consumers receive advice, the advice is suitable and takes account of their circumstances.

- Consumers are provided with products that perform as firms have led them to expect, and the associated service is of an acceptable standard and as they have been led to expect.

- Consumers do not face unreasonable post-sale barriers imposed by firms to change product, switch provider, submit a claim or make a complaint.

There is plenty of evidence that house builders and estate agents are failing to provide many of these outcomes for home buyers and that home buyers are suffering as a result. Why does such an arcane, confusing contract as a residential leasehold have almost no regulatory oversight over how it can be marketed and sold, whilst simpler lower-risk financial contracts are subject to many times more regulatory scrutiny?

Advertising of Leasehold Properties

Rightmove had 76% marketshare among the UK’s top online property portals in 2018. They have a 30-page Technical Guidelines and Data Quality Requirements guide for agents posting listings with rules like “make sure images are of the property being advertised” and “only list a property as available if it really is available”. However there are no rules around advertising leaseholds. As such many properties for sale on Rightmove do not even state whether they are leasehold or freehold (nevermind critical information like lease length and conditions). Rightmove are advertising properties that have complicated financial contracts attached without disclosing this fact! Prospective buyers are forced to take initiative in asking agents about tenure type and conditions and as such less knowledgeable buyers often don’t understand the implications until after contracts are signed. It would be unthinkable for a lender to sell a loan to an individual without clearly disclosing the interest rate and penalties to borrowers — that’s why you see those big “APR” boxes in credit card and loan adverts. But if you buy a leasehold you are expected to know all the right questions to ask to make sure you don’t get exploited.

An example of an FCA-regulated personal loan advert with the interest rate clearly stated

I’m hopeful that the outcome of the Law Commision investigation into leasehold reform is that leaseholds are banned in England and Wales and that a sensible way to give freehold rights back to leaseholders is legislated. However if we don’t get this, then at the very least the sale and marketing of leaseholds should be subject to the same consumer protections that we have in place for similar financial contracts. As it stands you have far more consumer protection buying insurance for your phone than a leasehold property.